How to make climate change a vote winner in India

Why it's worked in the US and what it takes to bring all Indians on board

Welcome to the very first premium edition of Lights On, a newsletter that brings you the key stories and exclusive intel on energy and climate change in South Asia.

We now are a small but strong community and I can’t wait to share all the ideas and stories I am working on with you all!

Please keep sending ideas and let me know what you would like to see more of - you are shaping the Lights On community and this project as much as I do.

Man reading a newspaper. Darjeeling, India - Image Credit - Flickr/Seb.p

As this year’s most awaited elections draw to a close, many wonder about the part that climate change worries played in persuading Americans to vote one way or another. Researchers I spoke to are ready to put the question to the citizens once the results are final, but for now, they say, “it’s too early to know”.

One thing is certain: in the US, climate change was on the ballot. For the first time, candidates were asked about it during the presidential debates, and the Democrat Joe Biden put climate action at the centre of his $2 billion plan to ‘build back better’ after the Covid recession.

During election night, the right wing cable channel Fox News included questions about climate change and clean energy in its voter survey, showing that people are generally worried about the impacts of global warming and want to see the government invest more in clean energy.

Um, Fox News says 70% of voters want the government spending more on green energy. I think we might be winning the messaging battle on this one.

2,747 Retweets21,789 Likes

This year’s US election has come at a time of unprecedented crisis, and the Covid response has likely been a deciding factor in the minds of voters, but one thing remains certain - climate change now carries huge political weight in a country that has started to witness its unmistakable impacts on communities and the natural environment.

The climate message doesn’t stick

But climate vulnerability, as much as it unfolds in front of our very eyes, doesn’t always translate into political action. And this in turn means that some governments are less preoccupied about it. Take India as an example.

According to the non-profit Germanwatch, India ranks fifth for climate vulnerability among 181 countries, a ranking that captures loss of lives as well as financial damages from extreme events. These are not just numbers - it’s the 2018 heatwave that killed hundreds of people across the country, it’s the Chennai water crisis in June 2019, when all reservoirs around the city dried up. It’s melting Himalayan glaciers and crop failure.

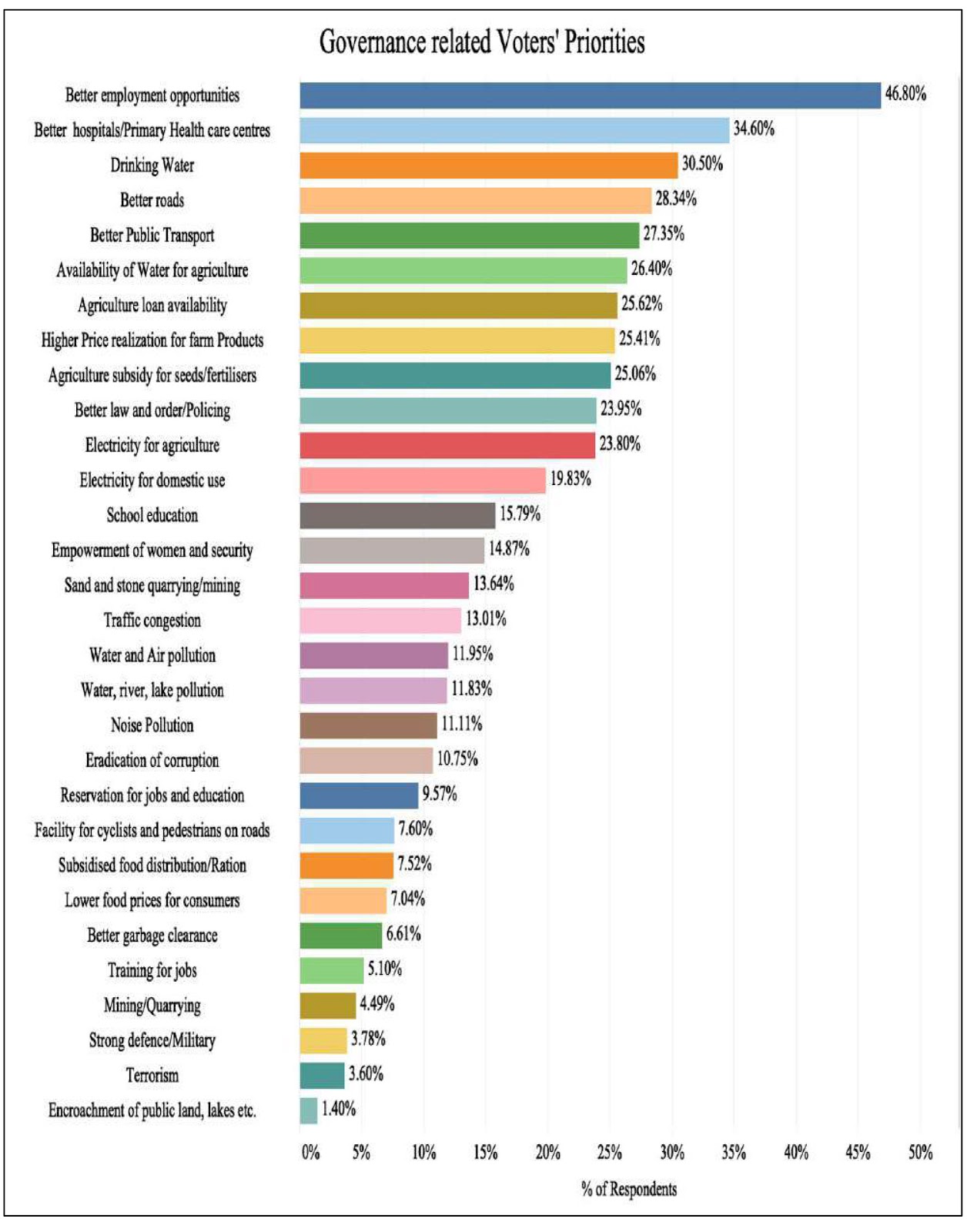

And yet, climate change remains eminently absent from the political conversation, despite India having a ministry officially devoted to environment, forests and climate change. In February 2019, the independent Association for Democratic Reform (ADR) surveyed 270,000 citizens across all states, the biggest sample ever in a single country, to gauge their concerns and how they feel the government is addressing them. Climate change response wasn’t even an issue included in the otherwise detailed survey, and no respondent mentioned the issue when given the chance to add to the questions raised.

Image credit: ADR - from the report All India Survey On Governance Issues and Voting Behaviour 2018

Environmental issues such as water and air pollution feature pretty low too, just above noise pollution, albeit slightly higher in the priorities of rural voters.

A different language

“Whether you call it climate, or ‘humans crossing boundaries of nature’, whether that happened due to Covid in some countries, including India, those boundaries are getting blurred, and the risk perceptions are becoming stronger,” says climate strategist Aarti Khosla, founder and director of the Delhi-based consultancy Climate Trends.

In a study published earlier this year by a team composed from Yale, the UK’s University of Westminster and Massey University in New Zealand, the authors found that while people in the US, UK and Australia associate the idea of climate change with images “psychologically distant in time and space”, such as melting glaciers or impacts on animals, Indian respondents associated climate change with “don’t know”, “pollution” and “heat”.

About a quarter of the respondents said that they “don’t know” or “can’t say”, when asked about global warming, suggesting that “global warming” or “climate change” are expressions that most Indians just can’t relate to.

According to Khosla, this is down to a couple of main factors: “First, it’s just our demographics as a country, a large part of our population is rural. Those are people who are very close to the impacts of climate change, but are not empowered to be able to raise their voice,” she says. For example, “even if events such as drought happen year on year in Maharashtra, the link to climate change has not been made so strongly in the elite discourse.”

In an op-ed for The Wire, columnist Anushree Joshi goes a step further, pinning the failure to create a mass climate movement on India’s cultural divide:

Breaking free from the Western lens

Because India has a multiplicity of languages, and only a small percentage of the population speaks English, “the trickle down [of climate change information] happens very slowly, or sometimes stops and does not happen,” Khosla says. “What gets covered in the elite English media will not land in Hindi and other regional press unless you make an effort.”

And sometimes, she adds, just translating the concept does not work. “The other problem with climate media is that [stories are told with] a very Western perspective. Even if you translate a story and put it in the biggest newspaper in the Hindi belt, it won’t make an impact unless you contextualize it.”

The climate conversation in the West is shaping up to be about issues that are very theoretical or just far away. Such is the essence of a problem that Western countries have created but don’t suffer from as much as the developing world. But climate action and the energy transition cannot happen in one part of the world only. To become truly global, the climate movement needs to speak to everyone - so it can translate into political action.

“It's about what is happening in my community, near me: air pollution, water scarcity,” Khosla says. “If you look at the impact of climate change on agriculture, drought, floods, these things have a lot of value, because in our rural hinterland half of the population is agrarian. But nobody has had the time and [put in the] effort to make it interesting or useful for them.”

When an idea such as climate change is lost in translation, people's lived experience versus what you're trying to tell them are stacked against each other, Khosla says.

“And unless the Western lens is replaced by my community’s perspective, that idea is never going to be empowering people to be able to demand something out of it.”

That’s it for today! Watch out for the Sunday read, and if you enjoy this newsletter, encourage your friends and colleagues to subscribe. Remember if you work for a company in the climate and energy sector you can expense your subscription: